Binging Buñuel: L'age D'or (1930)

The 1930 Buñuel-Dalí collab that broke up the band and was banned for fifty years.

At first L'Age D'or tries to pass itself off as a nature documentary. It then shifts gears and becomes a demented screwball slapstick rom-com. It concludes with allusions to a murderous, blasphemous, orgy. Somehow, somewhere, Luis Buñuel shoehorns what he says is the central theme: “passion, . . . the irresistible force that thrusts two people together, and about the impossibility of their ever becoming one.” During the chaos of its creation and early existence, the collaboration permanently damaged Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s friendship; chronic fissures formed within the surrealist body; and disgust and outrage over the film led to French rightists trashing a theater and destroying an accompanying surrealist art exhibition. The film became so toxic that it wouldn’t be publicly shown again until the 1980s. There’s a lot to unpack there, so here it goes.

From the success of Un Chien Andalou, Luis Buñuel gained a small profit and a lot of confidence. He was feeling a stronger pull down towards the surrealist path. The initial concept for his next film, L’age D’or, would be to string together gags he had been jotting down. These visual gags ranged from the sly social commentary of “a cart laden with workers rumbling through a literary salon” to the morbid slapstick of “a father shooting his own son because the boy dropped cigarette ashes on the floor.”

By the end of 1929, he had secured financial backing for the project through the auspices of Viscount Charles de Noailles, a French nobleman and patron of the avant-garde arts. The Viscount was also involved in establishing Dalí’s art career—as by this time, his pieces were beginning to be highly sought after by serious collectors (Mary McAuliffe, 2018).

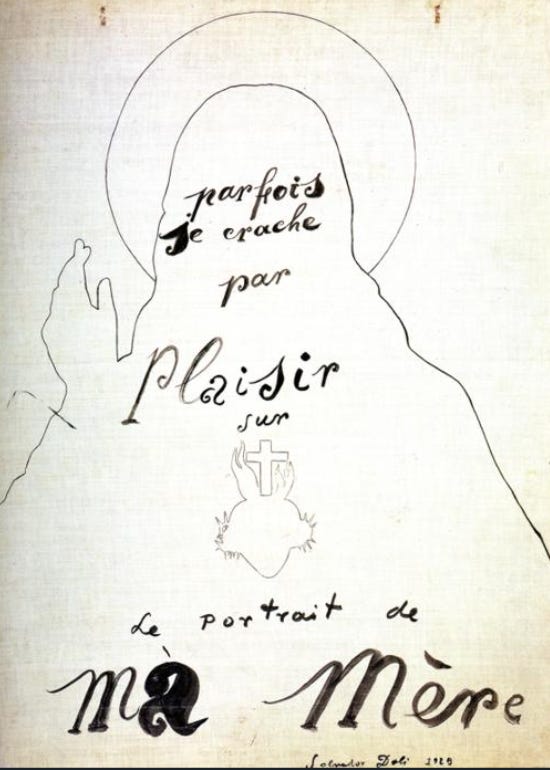

With the funding set and creative freedom guaranteed, Buñuel sent Dalí a letter on the eve before the dawn of the thirties saying that he was in Spain and was eager to collaborate on the new film. What Buñuel found once he tried to reignite their collaboration was that their sympathetic working relationship was becoming more strained and volatile. First of all, Dalí’s chaotic life interfered with his productivity and availability. There were issues with his father, revolving around his son’s affair with surrealist poet Paul Éluard’s wife, Gala, and the scandal of a Dadaist style piece which Dalí had provocatively titled Sometimes I Spit with Pleasure on the Portrait of My Mother. Gala rubbed Buñuel the wrong way as well, further exacerbating the working relationship. She had become integrally meshed with Dalí’s life and art. She became his focus and muse from the time they met in the summer of 1929, through their eventual marriage, and until her death in 1982. Dalí was more and more preoccupied with establishing his own art career, meaning the two Spanish surrealist confederates were headed down divergent artistic paths. Their initial synchronicity on Un Chien Andalou crumbled under the weight of the personal chaos in Dalí’s life and the contentious brainstorming sessions, where vetoes outnumbered areas of agreement.

Buñuel has minimized Dalí’s contribution to the film, crediting him with one typically surrealist scene—a man walking through a public garden with a rock on his head passing a statue which has a rock on its head, too—but little else. However, modern film historians, such as Gubern and Hammond (2012), believe there is greater evidence of Dalí’s contributions due to correspondences containing script ideas and storyboards. In the end, Dalí is acknowledged on screen as a scenario co-writer, and his name will always be linked to the two earliest films Buñuel directed.

The stormy collaboration and the conflict of ideas are reflected in the film. It contains swells of unconnected images crashing on the shores of sensibility. If we dare to analyze the structure, themes, and action of the film, we can use a framework created by Paul Hammond (2003). He posits that there are six distinct sections to the film and that each section relates to a scorpion's tail and its five prismatic articulations, which are the jointed segments, and the poison sac at the tip. This is a clever way to place structure on a film that is amorphous in plot construction.

Let’s start with the first prismatic articulation: the scorpion documentary. Buñuel had a fascination with insects. He fancied himself an entomologist when entering the university of Madrid. His father, however, dissuaded him of this notion of studying insects, persuading him to study agronomy instead. This he eventually abandoned as well. Even though he did not continue the formal study of entomology, he would always use insects within his films—not just for symbolic purposes, but also for his own interest and amusement. Real scorpions were to be used to film these opening scenes. Logistics and time constraints kept the director from realizing this initial idea; consequently, Buñuel decided to repurpose a 1912 childhood educational film called Le scorpion languedocien (Hammond, 2003). With Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture playing in the background (Barlow, 2001), the documentary details the exoskeletal features of the arachnoid—the pincers, the articulations, and the poisonous sac. The descriptions of its behavior are dramatic and have a menacing undertone. He describes scorpions as antisocial lovers of darkness with pincers that are instruments of information and aggression. The final section shows a rat sacrificed to exemplify how deadly the aggressive insect can be. This is as an early instance of the sacrificial nature of animals in Buñuel’s art. These sacrifices are used to achieve artistic aims and can be connected to biblical sacrifices: bulls for the god Baal, Abraham’s son for the Old Testament god, and Jesus for the sins of man. From a twenty-first century perspective of animal rights enlightenment, disregard for animal life in Buñuel films is disturbingly common. I will be discussing animal sacrifice more in his next film, which presents more problematic examples of this theme.

In the second prismatic articulation, he toys with time, as he did in Un Chien Andalou, with the intertitle of “some hours afterwards.” He expands outward from the entomological to the anthropological by fading to a bandit on a cliff scanning a rocky outcrop below where four bishops are sitting giving liturgical recitations—the first example of Buñuel placing religious imagery in an incongruent situation in this film. As the bandit walks back and enters the lair, we have a close-up shot of the leader, played by Max Ernst. He screams the first words ever heard in a Buñuel film, “Stop it!”

Let’s take a moment to appreciate this minor landmark in film history: L’age D’or is one of the first talkies to be produced in France. To be sure, the film still depends heavily on intertitles, but within the span of a year, the evolutionary transition between silent and sound films can be experienced in the first two films of Buñuel.

Returning to the bandits, they all look ill, injured, and poverty-stricken. Later Ernst calls this ragtag group to arms because the Majorcans are coming. Who are the Majorcans? Why are they coming to this unnamed island? We don’t even know who these bandits really are, and we never do because they mysteriously never reappear after leaving to confront the invaders.

In the third prismatic articulation, the bandits are gone, and the Majorcans have landed: soldiers, officials, and civilians all dressed in their finest. They come across the outcrop with the skeletal remains of the bishops. They doff their hats in respect and move on to gather for a proclamation by the Majorcan head official. They are interrupted by the sounds of passion of our two main protagonists, played by Gaston Modot and Lya Lys, who are rolling around in the sand. The lovers in ecstasy are broken up by the crowd. They are the two that will never become one, and Gaston’s yearning is represented by surreal images of Lya, toilets, and lava flows intercut with his muddy and bloody face. This section ends with Modot being hauled away by two men and him escaping once to kick a dog and again to stomp on a beetle. What happens to the Majorcans? They all died in 1930. A stone marks the site of their downfall and commemorates the founding of Imperial Rome, the setting for the fourth prismatic articulation.

What is the connection between the Majorcans and Rome? Paul Hammond postulates it’s a commentary on a desire of Miguel Primo de Rivera, Spanish dictator from 1923-1930, and Mussolini, the Italian fascist autocrat, to create an alliance between these two Latinate powers. This would eventually lead to an Italian base in Majorca during the Spanish Civil War. Additionally, Codera and Dogliani (2022) state that during this time a naval alliance was considered between Spain and Italy as a counterbalance to French power. Rivera saw Mussolini as a role model and tried to emulate Italian style economic policies. These are reasonable interpretations. I also sense a refashioning of the myth of the founding of Rome. One of the intertitles describes the city as the mistress of the pagan world. Within that pagan past is the myth of Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Mars, suckled by a wolf, and raised by a shepherd. Romulus kills his twin, and Rome was founded on violence. From these pagan beginnings, it now houses the seat of the powerful Catholic church, the Vatican. The violence and the church are intertwined, and this fact is alluded to with newsreel footage of an aerial view of the Holy See intercut with scenes of invading modernity and buildings being demolished.

As we come down from the expansive aerial view of Rome, we are reintroduced to our muddied passionate hero, Gaston, being roughly escorted on the streets by the same men who took him from the beach. Advertisements play a role in this section as each one he sees reminds him of Lya. Each ad seems focused on a particular body part, giving sexual connotations and highlighting “the sex sells” aspect of advertising and consumerism: fingers gesturing sexually, masturbatorily; stockings showing off legs with the skirt hiked up seductively; and the final ad of a model's head leaning back glamorously. This final image morphs into Lya reclining on a settee in a house full of opulence. He is chasing something that is unattainable and where reality will never match fantasy, as we will witness later.

The images come fast and furious, and each is just as absurd as the next. So in true modernist-surrealist fashion, here’s a stream of consciousness list of the visual gags: A man dusting himself off in front of the patrons enjoying coffee at an outdoor cafe; another man kicking a violin down a street and then stomping on it; Dalí’s man walking with a stone on his head; Lys with a bandaged finger, maybe connected to the rapid finger movements of the ad; a cow on her bed which she shoos off it and out of the room; Gaston, now identified as a special delegate for the interior minister, kicks down a blind man to take a taxi; Lys’s parents plans for a party; and the Majorcans have been resurrected, set to arrive at the party at 9:00. More gags are to come as the party ramps up, which is the fifth articulated section.

There are a string of gags interwoven with the party scene which serve as a commentary of bourgeoise indifference to the lower class: the laborers riding on a horse drawn cart boozing through the party; the tender scene of a gardener-hunter and son turning deadly after the son smacks the tobacco his father had been rolling into a cigarette on to the ground; and the death of a maid caused by the kitchen catching fire. In each scene, the partygoers completely ignore each person of the lower class, or in the case of the father shooting his son, there is initial shock that fades as they resume the festivities.

The party scene is where Gaston and Lys finally meet up and come together. Dark perversions of the light slapstick comedies of Buster Keaton, Harold Lloyd, and Chaplin present obstacles that prevent them from consummating their desire: her mother spills wine on Gaston and he smacks her; when an elderly conductor strikes up Wagner’s Liebestod, the sudden abrupt jolt of sound interrupts their kiss; they accidentally butt heads with each other during another attempt at a kiss; he tries to pick her up and drops her; a phone call from the minister of interior sends him off to be berated by the minister; the minister commits suicide after hanging up, ending up lying dead on the ceiling. Her passion is so unconsummated that when he runs off to answer the phone call, she sucks on the toes of a statue. At the end, she falls for the music conductor, looking rather Leninesque, and is locked in arms and lips with him as Gaston leaves in disgust.

Finally, in a fit of exasperation and rage, Godot runs off to her room to tear the feathers out of her pillows and to throw out the following items from a window: a burning tree, a real-live bishop, an easel, and lastly, a toy giraffe into a primordial lava stew.

Now we have reached the poisonous sac. At the outset of this post, I had made mention of the film being banned. The liberties that were taken with catholic imagery—the skeletal remains of the bishops on the shore and the one being defenestrated—alone would alarm catholic groups enough to request that the film be banned (Aleman Gomez, 2020). Compounding these indirect attacks on Catholicism are the critiques and satirization of the bourgeoise. There’s also the bawdy humor and violence, which would trigger the moral police of the day. However, what angered the government, the rightists, the church and the bourgeoise the most was the sting of the poison sac. (Sorry, I couldn’t help myself.)

The toxicity takes the form of Buñuel’s interpretation of Marquis de Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom. Before I get into this last section of the film, allow me to briefly explain the surrealists’ relationship with de Sade. They were influenced by Sade’s anti-establishment life and transgressive writing. His work contained bits of philosophical meanderings on morality, sexuality, religion, and politics all the while exploring the seamy and explicit facets of human lust and desire. Surrealist poet Robert Desnos said he represented the “first philosophical and vibrant manifestation of the modern spirit,” a free-thinking revolutionary libertine. Breton made a brief reference to him in his first Surrealist Manifesto and in his second manifesto, expanded upon his idealistic view of de Sade as the libertine revolutionary while overlooking some of the more disturbing aspects of his work. Desnos and other surrealists and surrealist adjacent artists, were more interested in exploring the baser aspects of de Sade’s philosophy. The prime example is Georges Bataille who founded a sort of scatological philosophy based on the work of Sade and wrote in a very explicit style that conjured up the sadistic side of the Marquis.

Similar to his intellectual and artistic contemporaries' reverence for the Marquis de Sade, Buñuel “was profoundly impressed by his recipe for cultural revolution” when first encountering his unfinished novel, 120 Days of Sodom. The Marquis was serving a decades long term of imprisonment on charges of deviancy and blasphemy when he created a tale of four libertines and their absurdly long orgy, which devolves into unimaginably gross descriptions of depravity and, coincidentally, lasts 120 days.

Buñuel presents a much tamer version of the story by presenting a summary of the activities through intertitles to introduce the post-coital aftermath. He sets the profanation to come by shifting the classical soundtrack to the steady rhythm of the drums of Calanda. These drums are part of a ceremony played during Easter for 24 hours beginning at noon on Good Friday. It was a ceremony that Buñuel himself had participated in. The drums are played to observe the moment of Christ’s death when, according to Buñuel in his autobiography, shadows covered the earth, the earth quaked, and rocks fell. They are also played to commemorate the rending of the temple veil—the veil that separated man from God and the high priest in the temple—allowing Jesus to become high priest supreme in order to offer salvation to Jew and gentile alike.

While these drums with such hefty significance rattle on, the godless and unprincipled libertines exit the Chateau de Selliny, a castle atop a snowy mountain. The four scoundrels, as Buñuel now calls them, are a duke, a bishop, a banker, and a judge. The first and most important to leave is the duke, Duc de Blangis.

We notice something peculiar about the duke. Blangis is played by a Russian actor, Lionel Salem, who bears a striking resemblance to the European representation of Christ with long hair, a beard and a repentant face, and curiously, holding his stomach as if he had a bad case of indigestion. As he leads his comrades in sin away from the castle, out comes a bloodied damsel in distress. Blangis returns to offer succor by lifting her up, caressing her caringly, and escorting her back through the fortress door. A few seconds later, her scream penetrates the din of the drums and Blangis exits with the same odd expression, sans beard. The film ends with the haunting image of the cross with scalps of the victims nailed on it.

So, there we have it: a tale pulsing poison through to the end. It was enough to infuriate the church, the bourgeoisie, and the moral right to the point of riot, which is what happened.

Initially, during the early private and public screenings of the film, L’age D’or was headed towards becoming the success that Un Chien Andalou had been. However, the storm clouds of scandal that were slowly growing erupted on the sixth showing on December 3, 1930. Members of the Ligue des Patriotes (the League of Patriots) and the Ligue Anti-Juive (the Anti-Jewish League) attacked Studio 28, where the film was being shown. They hurled antisemitic epithets, inkwells, and stones at the screen (Barlow, 2001). They also destroyed works by surrealist artists, such as Miro, Ernst, Ray, and Dalí, which were being exhibited in the lobby. Arrests were made and the censors demanded cuts to the films, most notably those involving religious imagery, if the film were to be screened again. Further pressure from the press and authorities led to the confiscation of the film, which eventually resulted in it not being shown publicly for fifty years (Hammond, 2003).

The demise of the film and the disintegration of the relationship between Buñuel and Dali intersected with the fractures among the ideological and philosophical goals of the surrealists. The divide between the surrealists was represented by Breton’s romantic idealism on one side and Bataille’s base materialism and darker Sadian obsessions with transgression and perversion on the other. Buñuel’s only mention of this rift between the two in his autobiography is that Breton “found Bataille vulgar and materialistic” while also commenting that Bataille had a serious, unsmiling face. Breton in his Second Manifesto of Surrealism more explicitly accused Bataille of focusing on “that which is vilest, most discouraging, and most corrupted,” effectively outlining his need to “excommunicate” Bataille and others, like Desnos, who supported him. Bataille accepted and reinforced this assessment by writing an open letter to his comrades, mostly likely Breton and his surrealist lot, in the Use Value of D.A.F. de Sade. Here he sketches out a philosophy based on scatology and revolution. The philosophical treatise on the power of excretion seems a pretty ridiculous read, but these ideas were a major driving force on shaping his perspective on the world.

There was a lot of disillusionment going around in surrealist circles as the above-mentioned fissures were taking place. The active destruction of art and freedom of expression being upheld by the state was alarming. Fascism was tightening its grip in Italy, Buñuel’s homeland of Spain, and most ominously, Nazi Germany. The luster of the Marxist and Communist ideal of the Soviet Union was being tarnished by Stalin’s dictatorial tendencies. Within this climate and as the 1930s marched towards certain war, Buñuel would court controversy again with his next film: Las Hurdes/Tierra sin Pan (Land without Bread).

References

Alemán Gómez, M. Á. (2020). Spanish Censorship and Buñuel's fim L'Âge d'Or. Revista De História Da Arte.

Barlow, P. (2001). Surreal Symphonies. In Soundtrack Available: Essays on Film and Popular Music (pp. 31–52). Duke University Press.

Bataille, G. (1986). The Use Value of D.A.F. de Sade (An Open Letter to My Current Comrades). In A. Stoekl (Trans.), Visions of Excess. Selected Writings, 1927–1939 (pp. 91–102). University of Minnesota Press.

Breton, A. (1969). Manifestoes of Surrealism (R. Seaver & H. R. Lane, Trans.). The University of Michigan Press.

Buñuel, L. (1985). My Last Breath (A. Israel, Trans.). Fontana Paperbacks.

Codera, M. F., & Dogliani, P. (Eds.). (2022). Continental Transfers: Cultural and Political Exchange Among Spain, Italy and Argentina, 1914-1945. Berghahn Books.

Gubern, R., & Hammond, P. (2012). Luis Buñuel: The Red Years, 1929–1939. University of Wisconsin Press.

Hammond, P. (2003). L’age D’or. In British Film Institute Film Classics (1st ed., pp. 115–137). Taylor and Francis.

McAuliffe, M. (2018). Paris on the Brink: The 1930s Paris of Jean Renoir, Salvador Dalí, Simone de Beauvoir, André Gide, Sylvia Beach, Léon Blum, and Their Friends. Rowman & Littlefield.