"Give me two hours a day of activity, and I'll take the other twenty-two in dreams . . . provided I can remember them." Luis Buñuel

Watching Un Chien Andalou is like watching a dream, or more like a nightmare. Dreams, their representation and interpretations, were a core component of the surrealist approach to art, and you can’t talk about Buñuel and this film without talking about surrealism. In his book, My Last Breath, he says “the pleasure of dreaming-is the single most important thing I shared with the surrealists.”

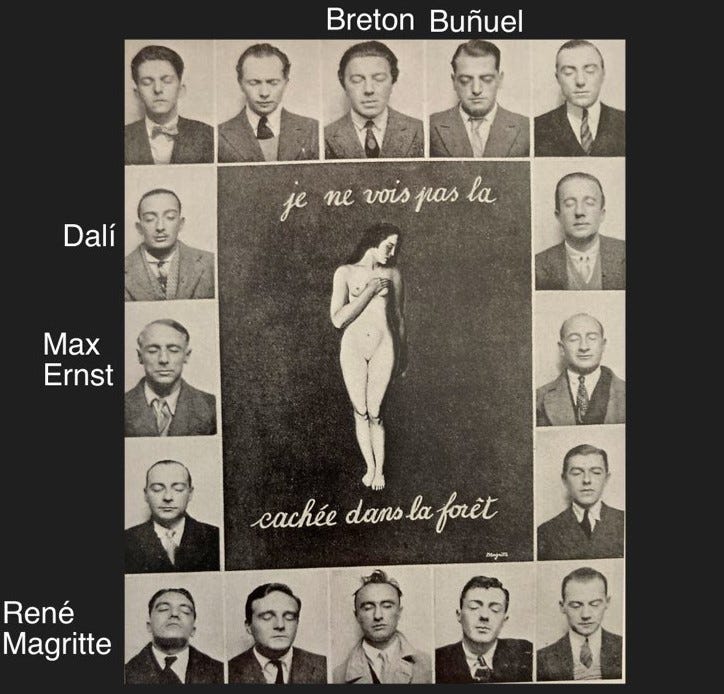

The movement of Surrealism grew out of writer Andre Breton’s interest in Freud’s psychoanalysis of dreams. In his 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, Breton defined Surrealism as a means to "express [through art] the actual functioning of thought . . . in the absence of any control exercised by reason, exempt from any aesthetic or moral concern." Buñuel's goal with this film was exactly that: represent a dreamscape, detached from reason or time.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, many artists were practicing what Buñuel called “instinctive forms of irrational expression” before knowing about or becoming involved in larger more coordinated artistic movements. These forms of irrational expression stemmed from the radical changes in society, technology, and thought. We had machines which could capture images both still and moving; machines which carried voices through wire or the ether that we could actually listen back to and respond to; machines which could carry us across or above continents in hours or days; and machines that could brutally massacre at unprecedented levels by the time the First World War rolled around.

Art and literature reflected this turbulence and upheaval by upending traditional structures of narration and form. Literary Modernism and its visual offshoots, such as Dadaism and Surrealism, incorporated ideas by revolutionary thinkers like Freud, Darwin, Marx, and Nietzsche in order to reflect their fractured shell-shocked society. Modernists like Joyce and Woolf wanted to represent the questioning of life, religion, politics, and sex through stream of consciousness thought on the written page. Dadaism and Surrealism emulated a similar aesthetic. The art created was criticized for being ugly, perverse, and blasphemous. As an example, the Dadaist, Marcel Duchamp, submitted a urinal as an art piece in 1917 that was suppressed by the exhibitors. That work still lives on, however, as a statement of what can be considered art. It represents art’s ability to shock, repulse, and question the establishment while inspiring others to do the same.

As I mentioned in the intro, exploring instinctive forms of irrational expression was in the artistic zeitgeist during Buñuel’s time at the University of Madrid. He would link up with similar minded schoolmates, namely Federico García Lorca, the renowned poet, and Salvador Dalí, who would become the most recognizable name in Surrealism.

In 1925, Buñuel was lured to France in order to work for the post WWI organization, and United Nations predecessor, the League of Nations. That job never panned out, but his path towards filmmaking was set when he ended up writing movie reviews and assisting Jean Epstein in making a couple of classic silent films, Mauprat and The Fall of the House of Usher. Jean Epstein and his assistant eventually had a falling out during the second film. Epstein warned the young Buñuel before dismissing him, "I see surrealistic tendencies in you. If you want my advice, you'll stay away from them." He didn’t. In fact, the film that he and Dalí would make would gain them entry into the movement and be considered amongst the most important surrealist works.

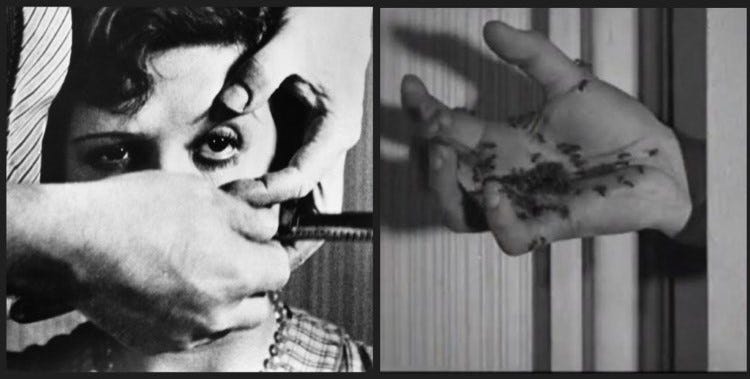

After the falling out with Epstein, Buñuel visited Dalí in Spain. They were discussing dreams when Buñuel described one in which “a long, tapering cloud sliced the moon in half, like a razor blade slicing through an eye.” Dali responded with an account of his most recent dream about “a hand crawling with ants.” With those basic images as the basis for a film, they had a script within a week. Bunuel, knowing no rational production company would fund a film based on a bunch of dream sequences, asked his mother for financial backing. Moms being the supportive beings they can be—she reluctantly ponied up the cash. Buñuel went back to Paris to begin shooting the film, and Dalí would later join him near the end of the two-week shoot.

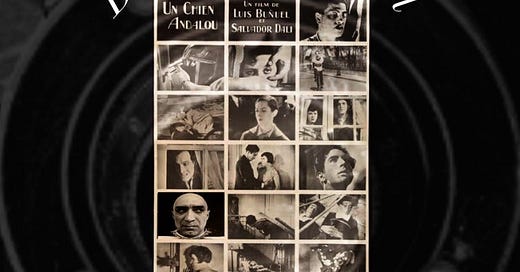

To describe the plot is difficult as there is no discernible one. Each section is introduced by an intertitle card with different time periods that are unconnected to each other: once upon a time, eight years later, around three in the morning, sixteen years ago, and in the spring.

Following the intertitles are sequences of events related to the dreams both Buñuel and Dalí had. The eye slit and the ants are represented as well as a few others I mentioned in my previous post.

They put to screen images about our desire to experience the cruel and absurd: rubbernecking onlookers at the sight of an accident; sexual deviancy and fetishism; and religious symbolism in incongruent situations. The latter for example is best represented in the scene in which actor, Pierre Batcheff, rides a bicycle in a nun’s habit while a striped box hangs around his neck.

According to Buñuel, Dalí came near the end of the filming to prepare for a scene involving the protagonist dragging dead burros. He prepared the burros, and together they dressed up as priests to be dragged across the floor behind two pianos with the stuffed donkeys caked with blood—another example of incongruous religious imagery. The final shot looks very reminiscent of a style of matte painting Dalí would be later be known for: lovers dead and buried up to their bellies in a sandy landscape au printemps.

The film was shown as the first of a double feature with a film that photographer Man Ray had made. As the film played, Buñuel was behind the screen with a phonograph alternating discs of Argentinian tangoes and Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde.

With stones in his pockets, expecting to use them to battle the viscerally negative reception he was expecting, what he got was a prolonged applause by the likes of Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and most importantly, Breton. Invitations to surrealist group meetings soon followed, and the two men would be important contributors to the movement.

This short film is open to interpretation. The title doesn’t help much either in that respect. Translated to English, it means “An Andalusian Dog.” Neither the Andalusian region of Spain nor dogs are really referenced; although Lorca, an Andalusian, felt the title was an insult directed at him. Both Buñuel and Dalí denied it had anything to do with him.

What you get out of it will certainly be different from what I’ve gotten out of it. Reactions will fall within the continuum of amusement and disgust. Ultimately, what it does show is the work of two inspired young men to take what they felt was silly, absurd, ridiculous, and controversial and put these ideas within an art form that was still relatively new in 1929. They were able to encapsulate the surrealist aesthetic in 16 minutes; thus, entering the pantheon of surrealists and cinéastes.