Binging Buñuel: Las Hurdes: Tierra sin Pan (1933)

Buñuel's surrealist documentary that ticked off the government, sacrificed beast and truth, and left the subjects of the doc afflicted with the Black Legend that they still suffer from today.

I. Who are you ?

I used to watch bullfights on TV.

That’s because around the turn of the millennium, I spent a semester studying Spanish in Salamanca Spain. It was a formative moment in my life—a personal ethnographic attempt to connect to some part of my ancestral past and find out who I was and where I came from.

You see, I’m of Puerto Rican descent, born and bred in the United States, the present territorial possessor of Puerto Rico. As anyone who has even a slightly ethnic look to them knows, people are always trying to figure out where you’re from, or more insensitively, what you are, even though you speak English as well or better than the person asking. I guess that got drilled into my brain—being seen as from somewhere other than the US of A. Conversely, I was Puerto Rican, but rarely visited the island and, more embarrassingly, could barely speak Spanish.

My grandparents and great grandparents came over to the US mainland to look for work and to better themselves and future generations. They were part of a broader plan by the US government to help propel American consumerism by being the labor that was needed to prop up materialist post war values in the 1950s.

Once they arrived in the land of good and plenty, “Americans” placed on them the stigma of negative stereotypes that all newcomers have to endure. Though they arrived with this new baggage hoisted upon them in addition to what they physically brought with them, Puerto Ricans have been US citizens since 1917, so they had easier entry to the mainland compared to those trying to cross the hostile Mexican border or the rough Caribbean waters. Many foreign immigrants have been denied entry because of different languages, cultures, and complexions. Being American citizens, Puerto Ricans had to face some challenges, but the main one was scraping up enough airfare or boat fare to get in. Once any migrant or immigrant moves to a foreign culture, they’re always trying to redefine themselves within it. As a second generation descendant of “domestic immigrants” and as an American expat in my current place of residence in Japan, I am always straddling different worlds and forging identities across them.

Here’s another interesting genealogical tidbit: through a bit of family sleuthing, I was told that my last name had possible Arabic origins. If you are familiar with any Spanish history, you might know that the Moors invaded Spain in 711 through the Strait of Gibraltar and occupied parts of the country until the 16th century. Thus, the potential Moorish strain in my ancestral lineage always stuck in my mind and became one of the motivating factors, years later, to go to Spain, the former colonizer of Puerto Rico.

So, where was I from? What am I? Here are a few more broad strokes about me that can either clarify or muddy the picture. After high school, I drifted through my first unremarkable stint at college and dropped out after a year. I took the odd job here and there until I ended up as a postal worker, sorting mail by hand and machine—a financially stable, but soul numbing, existence. I knew there were more meaningful experiences to be had rather than to be chained to a career which I had nothing but apathy and disinterest for.

I plotted, saved, and went back to school in my mid-20s, where I found linguistics, the study of language. I’ve always liked learning about the intricacies of English, such as grammar and stuff like that. I didn’t really have a facility to learn languages, however, but understanding the mechanics and discovering the history of humankind’s unique method of communication helped me to formulate a future career path.

In my final year of college, I decided to study Spanish in Salamanca, Spain. Classes were in the morning; afternoons and evenings were free. On the weekends and on longer holidays, I traveled around Spain. I got to marvel at opulent cathedrals that had used the distinctive Moorish mosque architecture as their foundations in the southern province of Andalucia. I was physically absorbed into giant modern art installations at The Guggenheim in Bilbao in Northern Spain. I also got to see Jonathan Richman sing Pablo Picasso in a small club that only served cans of Budweiser in Toledo—a weird pop art clash of Spanish versus American underground sensibilities.

Salamanca was close to the border of Portugal, so I went there for a few days and circled around to Sevilla in Andalucia. I even traversed the Strait of Gibraltar to North Africa twice—once to the Spanish territory of Ceuta and a couple of days later to Tangiers in Morocco. I blended in much more, at least appearance-wise, in this Mediterranean-North African band. It wasn’t until I opened my mouth to speak when people realized I wasn’t from around those parts. A couple times I got a more polite version of “What are you?” when they asked, “Are you French?” My accent was odd but not the gringo Spanish that Spaniards would expect from an American.

In Lisbon, people were asking me for directions, which I couldn’t answer because I neither knew the area nor the lingo. On another day, some young kids approached me asking me something in Portuguese. When they understood that I didn’t understand, they asked me in English if I wanted to buy drugs. I declined.

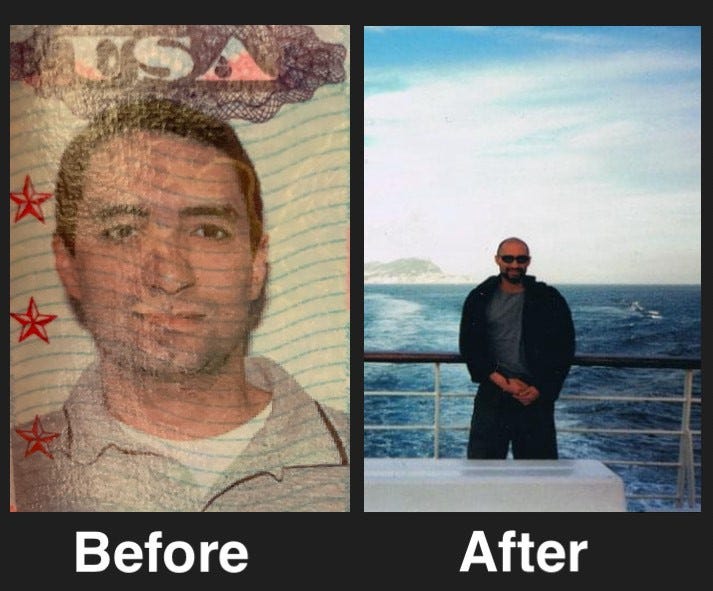

In North Africa, where my looks could condemn or save me, I had a mixed bag of positive and negative experiences. At the port of Ceuta, for example, the Spanish border authorities almost prevented me from boarding the ferry for my return journey back to mainland Spain. The guard didn't believe I was American. Again, it was another case of where are you from and what are you? Admittedly my passport picture had a clean-shaven face and a head full of curly hair. The version of me on this journey was a photo negative—a shaven head and a somewhat manicured beard. I was also donning a black PVC jacket and dark sunglasses, which may have aroused unwarranted suspicion. After a five-minute argument, which started in English and ended in Spanish, I convinced him that the person on the passport photo and the man arguing with him in a couple different languages were one and the same.

When I later went to Morocco, the unemployed mass of the male Tangier population—for unemployment was up to 20% at the time—were trying to pry cash from me by offering to guide me around or giving me some sales pitches for items I neither needed nor wanted. These pitches were a multilingual strafing to see which one would hit: Arabic, French, Spanish and English. I quickly learned to keep my mouth shut and keep moving.

On the positive side of my experience in Morocco, I was able to stay in line to get food at the canteen on the return ferry to Spain. The sun was going down and two young female travelers of Caucasoid extraction were turned away because the people in the line hadn't eaten all day. They were observing Ramadan. My looks and quiet demeanor allowed me to go unnoticed. I broke bread with the observant Muslims, who were surprised I didn’t know their language, food, or customs. They were very helpful in assisting me to navigate all three. They explained the dishes available on the menu, in Spanish, the language we shared. We shared a certain phenotype as well and with that combined with the kindness of the people around me, I was able to select and enjoy what would be my final Moroccan meal.

One impactful image that has always stuck with me, was of the caught stowaway, a young Moroccan kid, who had been hiding within the machinery of that same ferry and was escorted off by the border police. His skin was blackened by soot and desperation to leave the poverty of North Africa and make his way to “prosperity” in Europe. He had the same dream that the elders in my family had but without the means, for example a US passport, to easily achieve that dream.

Throughout this personal ethnological sojourn—interacting with people who looked like me, but didn’t necessarily share a similar culture or background as me—I didn’t find out who I was exactly, but I broadened the range and extent of the possibilities of who I could be.

II. Bullfights and BS

Like I was saying before, my classes finished in the early afternoon. It was a rush to get some food or head to the bank before everything closed down for siesta, which was from 2:00 to 5:00. On those afternoons, I would sit at my apartment and watch the bullfights on tv.

It is a bloody, brutal sport where the bull suffers the most. I was pulling for the bull because the rules of engagement were invariably weighted towards the matador. The bulls had no choice in the matter. Even though every once in a while, the matadors would get gored to the point I worried whether they had survived or not, I rarely rejoiced in his defeat. Nevertheless, I was transfixed by this spectacle and spent many afternoons watching this “sport” while waiting for siesta to end and evenings to begin.

If you’ve never watched a bull fight, here are the basics. There are three stages. Each stage is designed to slowly wear down the bull. The first stage features picadors, lancers astride horses, which jab spears at the animal to weaken it. The next stage involves other toreros called banderilleros. These toreros enter the ring and stab more lances into the back of the beast. These lances have colorful ribbons tied to the end and usually stay lodged on the bull’s back for the duration of the fight while blood seeps from the wounds inflicted. Finally, the matador, which literally translates to the killer, does the dance with the cape that everyone is familiar with. What everyone might not know is how it all ends. The weary bull, on the verge of collapse, stares down the matador in resignation. Then he lifts a sword in an aesthetically masculine pose and thrusts it through the skull of the animal. Its legs buckle and the muscular mass of the bull drops to the ground—lifeless. The mastery of a quick kill earns the matador a high distinction. Of course, the killer receives a rousing ovation from the audience as the poor beast lies dead with its blood soaking into the sandy arena. According to my Spanish history teacher, the meat of the bull killed in a bullfight was prized and commanded a high price because of the sacrificial role it had played.

The anthropological-ethnographic side of me always wonders: “Why are we humans willing to create artificial enmity and battle animals, in a kind of sacrificial rite, for sport?” Perhaps it stretches back to the days when humans wanted to appease and divine god’s will through animal sacrifice (Ekroth, 2014). Think of the sacrificial nature of domesticated animals such as cattle, goats, and sheep in the Bible. Muñiz and Muñiz (1996) document the prevalence of animal sacrifice, in particular taurine, or bull, sacrifice within diverse cultures from antiquity. There is archaeological evidence that suggests the roots of Spanish bull worshipping stem from pre-Roman Iberian culture and vestiges of Mithraism, a Roman religious cult which competed with Christianity in its earliest days of formation. Bull sacrifice is not only meant to divine god’s intent but also to transfer taurine potency to further strengthen the will and cultural binds of the Spanish people. This distinctive aspect of the Spanish psyche, with its neolithic heritage, was on display in televised form. I was witness to it as an unknowingly amateur ethnologist.

This circuitous path through some experiences related to my time in Spain tangentially intersects, as we slip through a temporal shift, to events that took place almost a century ago and 100 kilometers away from Salamanca. It’s an event that was to document the poverty of an area of Spain that was as crushing, if not more so, than that which I had superficially observed in Morocco. Within this document, the animal sacrifice aspect that is displayed is tied to archaic cultural customs. But also, in the hands of the documenter, it becomes an artistic means to an end, which is still being debated. The legacy of his style of ethnography affects the culture as it is seen today within Spain. This deprived society wound up being a sacrifice for his artistic aims. This culture, which suffers from the stains of a loss of dignity because of this document, is still trying to remove these blemishes and create a new legacy of who they are. This document is Luis Buñuel’s third film, Las Hurdes: Tierra sin Pan.

III. Las Hurdes: Tierra sin Pan

After completing L’age D’or, Buñuel decided to film a documentary about the people in a land in the northern part of the Caceres province, which borders Salamanca. This area is called Las Hurdes, and its people are referred to as los Hurdanos. Buñuel’s inspiration for wanting to document the lives of los Hurdanos was his fascination with a 1927 ethnography written by Maurice Legendre, Las Jurdes: Etude de Geographie Humaine. The poverty-stricken yet intelligent Hurdanos’ attachment to the “graceless mountains” and the sterile, “breadless” land—the tierra sin pan of the eventual title—intrigued him.

According to Buñuel, his friend Ramón Acín had bought a lottery ticket and promised the director that if the numbers hit, he would use the winnings to fund the making of the film. Ramón was an anarchist and social civic rights organizer during the turbulent pre-Spanish Civil War era of unstable administrations, which were veering from extreme left to right. He was full of altruism: he was active in providing education to the children on the lower rungs of society and wanted to better the lives of the Spanish poor in general. By documenting the plight of los Hurdanos, he would be able to shine a light on their situation in order to improve their lives. Incredibly, Acín won the lottery and kept his promise to Buñuel.

The documentary begins with the film crew’s journey through La Aberca, described as a wealthy feudal village, on the way to Las Hurdes. Their arrival coincides with “a strange and barbaric festival.” The festival involves recently married men riding horses through the middle of town. Roosters are strung up, hanging upside down on a rope which stretches across the main road. The young men take turns riding by and ripping off the cocks’ heads. Similar to the matador’s one strike kill of the bull, the goal is to smoothly separate the head from the body with one yank. The unfortunate ones who cannot achieve such a kill must make multiple attempts to complete the rite.

After witnessing this ritual, the crew moves on into the mountain villages of Las Hurdes. The landscape changes from the rich soil of Las Aberca to the barren breadless land of Las Hurdes. We are introduced to an abandoned convent and a monastery inhabited by a sole monk. Not only has nature deserted los Hurdanos but the Catholic God as well. Nearby, there are neolithic paintings of goats and bees on rocks, a foreshadowing of the artistic ritual slaughter to come and calling into question Buñuel’s actual aims with this film.

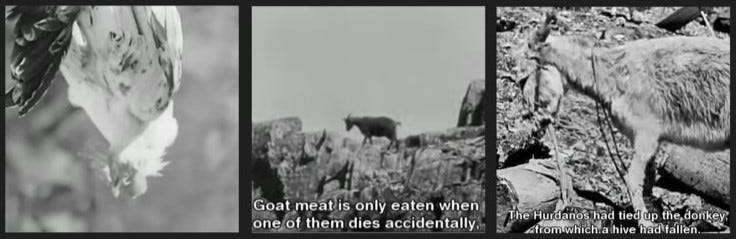

According to the narrator, los Hurdanos' diet consists of potatoes, beans, pork, and honey. They eat goat meat only when one dies accidentally. The camera then follows a goat descending a rocky cliff side. Suddenly, from the right side of the screen, a puff of smoke can be seen just before the animal falls to its death. We see the fall from a different angle from above as well and we begin to question the veracity of the content and the motivation of the filmmaker, as a goat is unlikely to plummet to its death twice.

Later in the film, the narrator explains that the main food industry is honey, though the hives are owned by the people of La Alberca. We learn about the supposed dangers of this type of work from the experience of a hitched donkey with a load of hives on its back. We are witness to the aftermath of the hives having fallen from the donkey: the bees viciously stinging the animal to death. The narrator reinforces the dangerous nature of this trade by stating that three men and eleven mules had been killed in the same way. Is the narrator a reliable source of information? I’d never heard of any dangers like this in the apiary industry, and the fact that Buñuel happened to catch such a gruesome accident on film leaves the viewer questioning again the reliability and the artistic impulses behind this documentary.

The initial motivation, as stated in Buñuel’s autobiography, was to film the lives of these people in the tierra sin pan. He needs to illustrate this fact—the rarity of bread in this barren land. He films a scene where children are dipping bread in a stream. The school teachers force the children to eat the bread in front of them for fear of the parents taking it away because it’s an unfamiliar food. Whether this fact presented is true or not will be debated years later as this is a key part of their portrayal that persists.

Additionally, the terms used to describe the people and their environment have also continued to stigmatize them. Buñuel had said that he was fascinated by the poverty-stricken yet intelligent Hurdanos. However, his descriptions never focus on their intelligence. Here’s a list of words and phrases used to describe los Hurdanos and Las Hurdes: They are inbred, deformed, destitute, and diseased. They have never heard a song and wear patched clothes. They suffer from choruses of coughs, goiter, dysentery, fatal infections, and malaria. The water available to them is a miserable little stream with repugnant filth in the bed where disease carrying anopheles mosquitoes breed. The misery doesn’t stop there. They also suffer from degeneration, poor hygiene, poverty, and incest. This final fact accounts for the prevalence of dwarves and cretins, here in its archaic usage of a condition of abnormal mental and physical development.

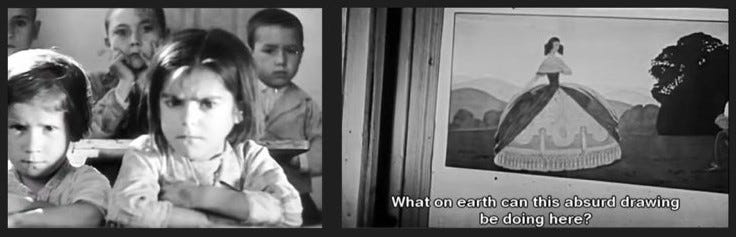

The narrator states that the children are starving, and many have been abandoned. These abandoned children, called “pilus,” are involved in a kind of trade where families “adopt” them in order to received government support payments. The accompanying images provide a vivid context for these descriptions. The effect was meant to evoke sympathy for the people and anger at a government that could let such poverty exist. That was Acín’s goal with the film. The portrait painted, though, may evoke sympathy yet it presents an unflattering one that verges on the absurd. The narrator references the absurdity by contrasting an “absurd drawing” hanging on a school room wall of an aristocratic woman in a 19th century cage crinoline petticoat, a dress with a wire frame, and the kids, many of them pilus, with shaved heads and bare feet.

As we were witness to the sacrifice of three animals, we indirectly witness the death of two young children. The first is a little girl who was lethargic and lying on the street. One of the crew inspected her mouth, and her throat and gums were swollen. At the time they could do nothing for her. Two days later they returned and asked about her. They were told she had died. The second is one of the final scenes—that of a mother and her dead child. The nearest cemetery is days away. Transporting the corpse to be buried is logistically complex. It is placed on a small wooden plank, carried through scrubland and floated down the river to its final destination.

Before the documentary ends, we are shown the only luxury afforded to the poverty-stricken hurdanos—a richly decorated church. It’s another contrastive image to add to the unfortunate absurdity and misery of the people. They are surrounded by the wealth of the citizens of Las Aberca and the church, but little is seemingly done to reduce their suffering. The movie ends on a final statement by an elderly hurdana woman. She says, “Nothing keeps you awake better than always thinking about death.”

Buñuel used los Hurdanos as artistic subjects and their tierra sin pan as a landscape to create a work of realism. The film is actually a work of ultra-realism (or sur-realism, if you investigate the etymological roots of the word, which later I will). It is much like the 17th century Spanish artists Francisco de Zurbaran’s Agnes Dei or Jose de Ribera’s Apollo flaying Marsyas, both of whom are referenced in the film.

Remember that Buñuel got his start as a surrealist filmmaker. If we analyze the etymology of the prefix “sur-,” it comes from Latin “super,” meaning “over” or “hyper.” With this film he created a hyper-reality of a people that one could not imagine. But if we also look at surrealism as the artistic concept of the 1920s, which I delved into in my first Binging Buñuel posts, it is defined as beyond reality, existence within dreams, impossibilities, and absurdities. Can this be true of this film as well? Is it actually a part of a surrealistic trilogy which includes Un Chien Andalou and L’age D’or? This film inhabits the middle part of a surrealist Venn diagram: the ultra-reality of the etymological roots of surrealism and the artistic absurdism of the surrealist movement.

There are many scholarly articles written about Las Hurdes surrealistic aspects. Part of this is to determine what was portrayed as false or staged. For almost a hundred years, film critics, film historians, anthropologists, and ethnographers have attempted to untangle the truth from fiction. Two films made within the past quarter century have tried to shed light on the making of Las Hurdes and its impact on los Hurdanos. Both condense much of the research done about the 1933 documentary in highly informative and engrossing films.

IV. Buñuel en el Laberinto de las Tortugas

The first one I'll discuss is 2018’s Buñuel en el Laberinto de las Tortugas (Buñuel in the Labyrinth of the Turtles) directed by Salvador Simó Busom. It is an animated retelling of the making of Tierra sin Pan. The film focuses on Buñuel and Ramón Acín’s relationship and how it became increasingly strained as their shared motivations for creating the film began diverging more and more. Acín as a social activist wanted a purer and more accurate depiction of the lives of the people. Buñuel, on the other hand, as an artist and surrealist, wanted a more dramatic representation, even if it meant sacrificing beast and truth. Let’s look at the examples of the animals being killed to further the dramatic and the sensational.

Apparently, the ritual in La Aberca is a real event; however, there is a close up of a chicken having its head pulled off that was staged. The film shows a strung-up rooster away from the festival set up for one of the crew to rip the head off in front of the camera. The men, the director included, were too chicken to do the deed. Instead, Buñuel paid one of the old men in the village to yank it off. In the case of the goat on the cliffs, the puff of smoke seen before the animal falls indicates a staged shooting. Buñuel fired the gun that toppled the goat from the cliff ledge. It was then dragged back up the hill so that the camera could capture it plummeting from the top angle. Finally, the hitched donkey that was stung to death had been smeared with honey before letting loose the bees upon it. This provided the impactful image of the poor creature writhing in pain towards its death.

With these scenes, the animation is intercut with the original ones from the documentary to emphasize the reality of the story, much like Buñuel’s supposed intention with sacrificing these animals in the first place. They are shocking in the original documentary and even more so when contrasted in an animated story that has a child-like quality to it.

While Acín wanted to show simply the natural suffering of the people, Buñuel was determined to heighten the reality, making it uber-real—surreal—to the viewer to show that death was at every corner. These scenes of animal sacrifice were meant to intensify life in Las Hurdes. A lamentable byproduct of these cross purposes was the increasing friction between Buñuel and Acín.

The very real deaths of the animals occurred; however, there were faked deaths as well. The prime example is the dead baby at the end that is floating down the river. The animation proposes that this was staged. There are hints in the original documentary that the baby was actually sound asleep. If one looks carefully, it can be seen breathing.

This film simply recounts the making of the documentary and questions, but doesn’t satisfactorily answer, the purpose of the animal sacrifices, the faked death of the children, and Buñuel’s overall intention with these stunts that would ultimately define los Hurdanos. The lack of definite answers may be because Buñuel himself never answered these questions. By the time there was significant interest in this film and its veracity, he had passed. Though we don’t know Buñuel’s purpose, we can deduce what it might have been.

The second documentary, Buñuel’s Prisoners, tries to provide a hypothesis as to why he made the film in the way he did. It does so in an intriguing way. It allows those most affected by Tierra sin Pan, los Hurdanos, to speculate how and why he portrayed them in the manner that he did.

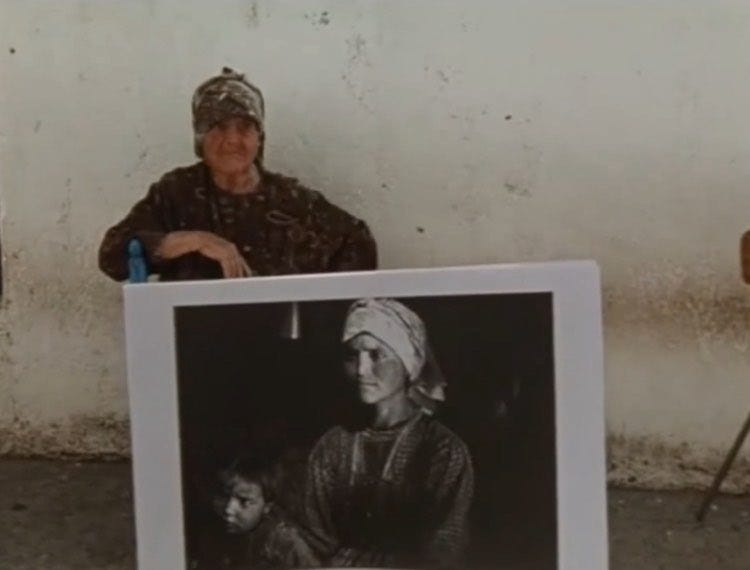

Ramon Gieling, the director of Bunuel’s Prisoners, created an event within the town of Pinofranqueado in the Las Hurdes region that he would use as a premise to gather the opinions of the people as to the veracity of the claims made in the original documentary. This event was a public outside viewing of the film to the inhabitants—a film many had never seen before, but the ramifications of its existence still afflicted them like a curse. This curse is known to los Hurdanos as Leyenda Negra, the Black Legend. Throughout the film Gieling interviews a wide array of residents about the Black Legend, including the mayor, elderly residents who can remember Buñuel’s visit to their town, and the youth who suffer from its repercussions.

We hear tales of how reality was distorted by the staged events. This distortion extends to the memories of the seventy and eighty-year-old Hurdanos as they were children at the time of the filming of Tierra sin Pan. There are conflicting recollections about facts and events. For example, some said bread was not so rare while others said it was only available on the few occasions it came in from Salamanca. The goat being shot is established as fact, although a short segment of the film is devoted to debating the exact location of where it happened. What needed no debate was the falsified reality of scavenged goat meat. Goat meat was eaten on a regular basis, and no one had to wait for one to fall to its death.

In regards to the facts surrounding the “dead child,” the evidence for the child being still alive is verified by those children from long ago. The additional fact that a cemetery was not days away but a ninety-minute walk from the village was another exaggerated truth for an unknown purpose. What could have shed more light on the scene was the fact the child’s mother, who appeared stoic and unflinching in the original film, was still alive. Getting her perspective on the scene would have been of great interest because of the climactic nature of the scene. However, her truth will forever be locked away inside her, because she is in a state of dementia and catatonia and cannot speak or remember anything.

As Gieling gains more insight on what was true versus what wasn’t, the most important outcome of the film is to show Las Hurdes now and to allow los Hurdanos to voice their opinions about Tierra sin Pan and how they were portrayed. They are bitter about the portrait painted in the film and have questions that can never be answered. The prime question asked: why was their area chosen? There were many parts of Spain that were struggling just as much as Las Hurdes.

The choice was made, however, and los Hurdanos must contend with the existence of the film and its growing notoriety. The ones who are the most critical view it as pure fiction, a farce, and a big lie, feeling they had been prostituted for whatever Buñuel’s aims were and that he did not have a high regard for the truth. A few of the more introspective interviewees said it presents an accurate picture of life at that time—80% to 90% of it is true—yet they are left wondering why the falsehoods and truth were mixed together in such a way.

Because of these lasting negative images, the young of today have to contend with the stigma placed upon them by the Black Legend. One young woman says their culture is blackened by the misrepresentation. When outsiders find out she is hurdana, they are surprised that a vibrant and intelligent youth comes from an area that has been contaminated by the negative connotations created by Bunuel’s film.

Despite the negative stereotypes placed upon them, they have a pride in their homeland. Though they may have been poor, and desperately so, joy existed. That joy was never portrayed. Additionally, those that are able to stand back and rationally consider Buñuel’s aims hypothesized that the director wanted to make the film more dramatic and gruesome so that it would be convincing and compelling. He enlarged reality to help the truth and indict the Spanish government. This indictment caused, once again, for another of his films to be banned.

VI. Buñuel Banned (Again)

Though Buñuel never accuses the Spanish government directly, it’s obvious that there is little governmental support for los hurdanos. The film indirectly condemns the wealthy residents of La Aberca and especially the Catholic Church for doing little to aid los Hurdanos. In targeting the bourgeoisie, as represented by the citizens of both La Aberca and Salamanca, and the church, the liberal administration of Alcala-Zamora tried to appease these two powerful groups by banning the film upon its release. As the Spanish Civil War began to ramp up and the Spanish government shifted from left to right in the mid-1930s, Franco’s regime continued the ban and monitored Buñuel, as he was working as a propagandist for the opposition, the liberal leaning republicans.

Ramón Acín was under scrutiny, too, because of his anarchist stance and support for the working class. The fallout of the ban, Spanish political turmoil, and his own communist and anarchist activities would be fatal for Acín. After avoiding capture by fascist right wing extremist, he was forced to give himself up after they had arrested his wife. As Buñuel succinctly describes his punishment, “the Fascists shot both of them.”

A common slogan amongst the falangists, members of Franco’s political party, was “Death to the intelligentsia.” Acín and his wife were unfortunate victims of this policy. Acín was not the only associate of Buñuel who was a casualty of the political upheaval and Franco’s desire to quell radical thought and speech. In 1936 Frederico Garcia Lorca, Buñuel’s university friend, would disappear and be assassinated as well.

As the outcome of the Spanish Civil War was slowly becoming assured, Franco would eventually claim victory and maintain a grip on Spanish political power for the next 40 years. At the same time, Europe was slowly turning towards fascism with the rise of Mussolini and Hitler. Buñuel was an artist who liked to stir up the bee hive. Seeing his likeminded friends and collaborators fatally stung for their efforts to criticize, undermine, or provide a counterpoint to the government’s repressive messaging and tactics, forced Buñuel to make the decision to make his way to Mexico as an exile, which would mark the next phase of his movie making career.

So where does all this lead: my formative trip to Salamanca, the bull fights, the animal sacrifice, the questions surrounding Buñuel’s artistic and political motivations for Tierra sin Pan, and los hurdanos contending with their portrayal.

We are here to shape the world as we see it. People looked at me and asked “what are you?” It forced me to define myself within the greater culture I was born into, the culture of my ancestors, and the foreign culture I exist within now. Buñuel asked who are los hurdanos. He defined them in such a way that they would have to confront that definition, debunk the falsehoods and use Buñuel’s sacrifice of animals and truth to strengthen their resilience and their cultural binds. By confronting their portrayal, the ultimate conclusion was that the impetus for creating Tierra sin Pan was an attempt at revealing ugly truths, and intensifying those truths, about the Spanish poor in order to better the conditions of the region. Finally, Buñuel would have to define himself as a Spanish exile within the context of a new culture--that of Mexico and Mexican cinema--where he would create his idiosyncratic art within a commercial template. Within this template he would continue to challenge and satirize the bourgeoisie and church, mostly subtly, but on occasion overtly. First, though he would have to understand what that template was.

References

Buñuel, L. (1985). My Last Breath (A. Israel, Trans.). Fontana Paperbacks.

Ekroth, G. (2014). Animal sacrifice in antiquity. The Oxford handbook of animals in classical thought and life, 324-54.

Muñiz, L. C. M., & Muñiz, A. M. (1996). The Spanish Bullfight: Some Historical Aspects, Traditional Interpretations, and Comments of Archaeozoological Interest for the Study of the Ritual Slaughter.

This is an excellent article - I knew about Bunuel's "documentary" but I didn't know the rest. Thanks for the insight! :)